Many articles I’ve read on instinct treat it as if it were synonymous with intuition, which has led to a popular definition common to both: an impression or feeling that seems true, even in the absence of logical reasoning.

Exploring human decision-making and the roles played by intuition and instincts is interdisciplinary work, involving fields as varied as psychology, neuroscience, educational science and anthropology. Each discipline approaches the subject from its own unique perspective, using different terminology and coming to its own conclusions. This diversity enriches our understanding, although it often groups the non-logical, the non-rational and the subconscious under the umbrella term of intuition. Here, I’ll share some key ideas to demystify intuition, offering ways to harness and refine it.

Instinct

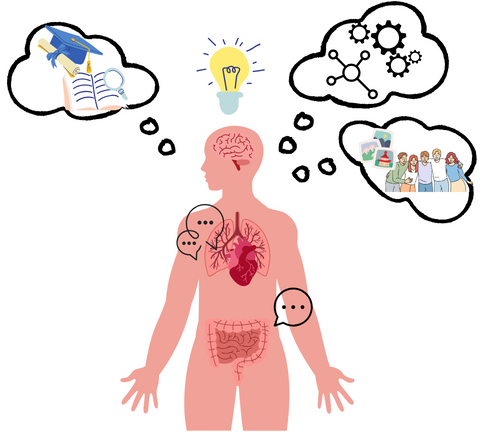

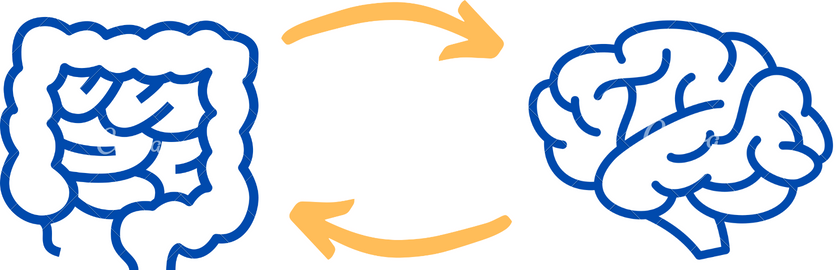

An instinct, often felt as a visceral reaction, arises from our instinctive understanding that something is right or not, or that a certain choice needs to be made. This experience is sustained by a sophisticated communication system between the gut and the brain. The enteric nervous system, also known as the “second brain”, is an intricate network of neurons that lines our gastrointestinal tract and sends signals to the brain, playing a significant role in shaping our emotions. On the other hand, the amygdala – an area of the brain that is part of emotional processing – can provoke a physical reaction in the body before the conscious mind has even had a chance to fully understand a situation. This dynamic exchange of information is what gives rise to the phenomenon we know as instinct, exemplifying the complex interaction between our physiological states and emotional experiences.

These instinctive responses may have served an evolutionary purpose, helping our ancestors to make quick decisions in the face of danger. For example, a feeling of discomfort when meeting a stranger can be an ancestral instinct that leads us to be careful. Although they don’t provide precise solutions, instincts can offer a general direction or alert us to potential risks, influenced by our biases and emotional states. At times when quick action is required, relying on these instinctive signals can be advantageous.

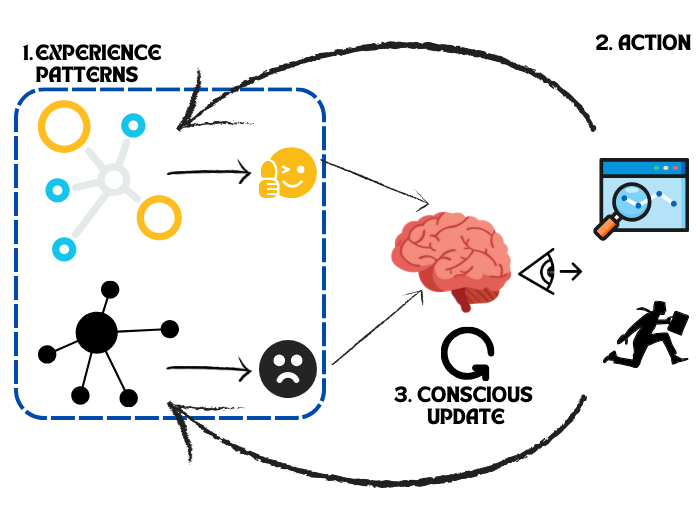

Intuition as Pattern Recognition

Intuition is a broad concept that involves an immediate understanding or knowledge without conscious processing of the information. Unlike instincts driven by emotion, intuition manifests itself through a sense of knowing, an insight or sudden clarity.

Throughout our lives, we accumulate a wealth of knowledge and experiences that are not always active in our thoughts, but reside in our subconscious. This reservoir of information shapes our intuitive decision-making, acting as a rapid pattern recognition system that draws on our accumulated prior knowledge to inform our choices.

This process can lead to decisions that seem inherently right without conscious explanation. Consider an experienced doctor who intuits a diagnosis before all the tests are conclusive, recognizing patterns from previous cases. Intuition, nourished by a variety of learnings and previous encounters, can be a reliable guide, especially in familiar situations. However, it is fallible, as it can be influenced by subconscious biases rooted in our personal interpretation of these experiences.

Linear Intuition and the Science of Meditation

Linear intuition, as conceptualized in ancient Hindu philosophy, transcends the familiar terrain of experience-based perception and subconscious pattern recognition. It suggests an ability to access a source of deep knowledge – a form of direct knowledge that often brings totally new insights.

Accessing this form of intuition is closely linked to the practice of meditation, also known as ‘dhyána’ in Sanskrit. The aim here is to stabilize the constant buzz of the mind, transcend the sensory and the everyday, and enter a state of deep concentration. In this state, the fluctuations of the mind are stilled, except for a single, unchanging focus.

From the point of view of modern neuroscience, the phenomenon of linear intuition remains enigmatic, but it has been observed that meditation promotes measurable changes in the brain:

- Sensory abstraction: The meditative state is characterized by a withdrawal of the impulse to act, as the connection with the sensory organs diminishes. Attention is present, but it is not fixed on sensory data. Neurologically, this correlates with a reduced firing rate in the thalamocortical pathways, indicating a reduction in the processing of sensory and motor information.

- Inner focus: Activity in the default mode network, associated with daydreaming and self-referential thinking, is reduced during meditation. This network is often active during rest and is known to deactivate when engaging in specific cognitive tasks. Simultaneously, the salience network, including regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula, becomes more active, highlighting the importance of internal sensations such as breathing (which can be a point of focus during meditation). This is complemented by the engagement of regions of the control network, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which facilitate sustained focus on these sensations.

- Altered brain wave patterns: Meditation is marked by an increase in alpha and theta brain wave activity, reflecting a state of relaxation and deep mental engagement respectively. Proficiency in meditation is correlated with increased theta wave activity in the frontal regions, indicating a deep meditative state.

Advanced practitioners show signs of greater neural efficiency, evidenced by a more effective exchange between states of brain connectivity. This reflects a refined ability to focus attention and resist distraction.

In short, while ancient traditions extol the profound potential of intuition accessed through meditative states, science is beginning to unravel the neural aspects of these experiences. During meditation, the mind is neither idle nor engaged in ordinary cognition, but in a unique state of consciousness that can foster the emergence of new intuitive perceptions. This is in line with the traditional view that intuition offers a different kind of knowledge, accessed not through intellectual effort, but through a deep attunement with the self and the universe.

Einstein is often cited for his approach to problem solving, which included periods of non-rational contemplation. His observations are famous:

We can’t solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

I think 99 times and find nothing. I stop thinking, dive into the silence, and the truth comes to me.

These thoughts are in line with the idea that understanding how our mind works can enable us to optimize it. Knowledge can emerge in various ways, enriching our mental, emotional and intuitive faculties. By practicing mindfulness, we become attuned to our instinctive feelings, subconscious patterns and spontaneous insights, learning to distinguish between intuition and emotion. This heightened awareness allows our intellect to explore new solutions and benefit from the full spectrum of our cognitive abilities, leading to more informed decision-making.

Practice for beginners

For beginners in meditation practices, I recommend starting with simple mindfulness exercises. These techniques involve focusing entirely on one task at a time. For example, during a workout, you can focus on the muscles you’re engaging; or at mealtimes, feel the flavors and textures of your food. Integrating mindfulness into your daily activities can sharpen your body awareness.

If you’re ready to dive deeper into improving your intuitive abilities, which can increase clarity, creativity and problem-solving capacity, meditation can be a powerful tool. Here are three accessible practices to get you started:

Find a comfortable position with your spine aligned, arms relaxed and hands resting on your legs, and gently close your eyes:

- Focus on your breathing. Observe the natural rhythm of your inhalation and exhalation without trying to change it.

- Select a piece of instrumental music and immerse yourself in its harmony. Choose a single instrument to follow and focus only on its sound.

- Visit a place with a panoramic view (such as mountains, a lake or a scenic sunrise or sunset) and simply contemplate the expanse of the landscape. Choose an element within the scene, such as the sun, and keep your attention fixed on it. Alternatively, you can close your eyes and focus on the mental image.

Keep exercising for 5 minutes or more. The change in perception can occur quickly for some, while others may need more time and practice. The key is consistency; the more you practice, the sharper your awareness becomes.

I encourage you to try these techniques and share your experiences. I look forward to discussing this further in a future article.

References:

Da Silva, S. System 1 vs. System 2 Thinking. Psych 2023, 5, 1057-1076.

Filippi V. Decision-making between rationality and intuition: effectiveness conditions and solutions to enhance decision efficacy. PhD dissertation, LUISS, 2019.

Craycroft K. Connecting the mind and body: Using embodied intuition as intelligence. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyväskylä, 2022.

Tripathi V. and Bharadwaj P. Neuroscience of the yogic theory of consciousness, Neuroscience of Consciousness 2021.

Ganesan S. et al. Focused attention meditation in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional functional MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022.

DeRose. Meditation and Self-Knowledge. Egregora Publishing House, 2019. English. Português- Français.